- Home

- Campaigns

- Research and policy

- Support to Work evaluation

- A co-produced evaluation of Scope’s Support to Work service

Support to Work is an online and telephone support programme for disabled people who are applying for jobs.

Jessica Bricknell, Amy Frounks, Ruth Murran and Giles Skerry

We would like to express our thanks to several people and organisations who helped make this co-produced evaluation possible.

Foreword from the Co-Evaluation Team: A note on coronavirus

This report presents an evaluation of Support to Work using data that describes customer and staff experiences from January to December 2019. But, we analysed data and wrote this report as Covid-19 spread across the UK.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed what employment looks like for many people. It has also affected how people access services. Scope has adapted many of its services to the new environment. It remains to be seen how permanent these changes will be, but we would like to briefly mention how Support to Work has been affected by coronavirus so far. We also consider the potential effects of coronavirus for disabled people looking for employment.

Support to Work and coronavirus

As a service normally provided through digital and telephone channels, Support to Work was perfectly positioned to continue providing its service into lockdown with minimal disruption. The Support to Work team started and continue to work from home.

During the first weeks of lockdown, fewer people than normal referred themselves to the service, though this drop in referrals was not as large as the ones seen in Scope’s face-to-face employment services. The number of referrals has since risen again, with the team receiving a record number of referrals in June 2020.

The service’s marketing has been updated to emphasise its remote delivery methods. The Support to Work team have also worked with Scope’s Information and Advice team to create new guidance on video interviews, which a lot of people looking for work will now experience as part of the application process.

During appointments, advisers have particularly supported customers with interview skills and preparation for starting work remotely. Support to Work customers are still successfully entering work during this atypical time.

The team have received feedback that the service has been a welcome source of structure to a home routine that has changed a lot. For those with caring commitments, it has been a time to focus on oneself and feel a sense of achievement.

Disabled people, employment, and coronavirus

We also wish to acknowledge the complex potential effect of coronavirus on disabled people and employment.

In one sense, coronavirus has increased workplace accessibility for many. Early in the pandemic, employers responded swiftly to set up or expand remote and flexible working practices. Now this precedent has been set, we would argue that it will be much more difficult for employers to deny flexible working and working from home as reasonable adjustments for disabled people. This could have a particularly positive effect on disabled people in remote areas, or in areas where accessible job opportunities are low.

The pandemic has also highlighted the importance of access to digital technology and skills to keep us connected and maintain wellbeing. We discuss in this report that digital access and skills can be a barrier for disabled people looking for work. We hope the pandemic has substantially increased employers’ and government’s awareness of and commitment to bridging the digital divide.

At the same time, as lockdown relaxes and financial support for employers and those who are shielding is withdrawn, people of working age who are shielding may come under increasing pressure to return to work. Many will face incredibly difficult decisions between their health and employment. The predicted recession is likely to have a significant effect on disabled people’s prospects of staying in work.

Along with the reintroduction of unemployment benefit sanctions and disability benefit reassessments, many disabled people will find themselves with little option but to seek new employment.

This makes services such as Support to Work more important than ever. Disabled people looking for work should have access to support from people who understand their challenges and will work with them to come up with strategies that suit their circumstances.

We are pleased to be publishing this report at such a critical time. We hope it provides a clear example of how the right support can lead to positive employment outcomes for disabled people – and how directly involving disabled people in developing that support can make it even more effective.

Scope’s Policy and Campaigns team will be using this evidence to directly encourage Government and local authorities to consider how they will support disabled people as the pandemic continues.

The Co-Evaluation Team

Executive summary

Support to Work is Scope’s national employment support service for disabled people. It supports disabled people who already have transferable skills and are actively looking for work. It is a fully remote service using telephone and digital tools and runs for up to 12 weeks. Each customer works with an individual employment adviser to develop and complete a bespoke action plan.

This report evaluates Support to Work using data from the calendar year 2019. It assesses the ability of the service to achieve its intended outcomes:

- Disabled people enter employment.

- Disabled people gain the knowledge and skills they need to choose, find, and apply for jobs.

- Disabled people become confident of their capability in work.

- Disabled people know their rights when in, or looking for, employment.

The research underpinning this evaluation has a unique approach and value because it has been directed and conducted by a team of people with lived experience of disability, as well as those with professional evaluation expertise. This has allowed Scope to embed the knowledge, experience, and concerns of disabled people into an assessment of the service.

Evaluation results

Who uses Support to Work?

Around half of Support to Work customers have been out of work for fewer than 6 months. Most customers have worked before. The customer base is more ethnically diverse and younger than the national disabled population. Many customers have had negative and sometimes discriminatory employment experiences directly linked to them being disabled. This leads to many customers feeling low in confidence when joining Support to Work.

What enables people to use Support to Work?

Support to Work’s simple, friendly sign-up process enables customers to refer themselves to the service. Its wide eligibility criteria contrast with some customers’ previous experiences of employment support. The most common route for people referring themselves to the service is via Facebook, where the service is promoted. 45% of referring customers find out about the service this way. These adverts are critical places for setting expectations about the service.

The combination of phone and digital communication tools increases the service’s accessibility. It allows customers to choose their preferred communication method. Furthermore, flexibility in arranging and changing appointments supports customers with fluctuating conditions.

What stops people from using Support to Work?

Not everyone who refers to Support to Work goes on to use it. Some customers refer themselves but don’t respond to service contact. Others are looking for work experience, or would be better suited to a face-to-face service, perhaps because they’re not confident in their digital skills. Support to Work signposts these customers to alternative services. Some customers also leave the service early. For many customers we don’t know the reason for this. For those who do provide reasons, there’s a high interest in accessing the service later on.

What does Support to Work achieve for its customers?

132 customers who exited Support to Work in 2019 entered employment after using the service. This is 23% of exiting customers. The most common amount of time a customer was on the service before moving into work was 5 weeks. Most customers moving into work have been out of work for fewer than 6 months.

Customers who don’t enter directly into employment also gain from using the service. Most customers develop knowledge and skills for various aspects of the job search process, as well as the confidence to put these skills into practice. Customers’ confidence in their own capability in work also grows.

Support to Work helps many customers develop a personal strategy for if, when, and how to talk to a prospective employer about their condition or impairment. Despite this, there is limited evidence of the service’s effect on customers’ knowledge of employment rights. This may partially reflect the tools previously used to measure this.

What do customers value most about Support to Work?

Customers value:

- the skills and experience of Support to Work’s employment advisers

- the service’s format and tools

- the central focus it places on tailoring to the individual.

The acceptance, understanding, and listening skills of advisers are particularly appreciated. So is their ability to offer new perspectives and ideas. The service provides helpful structure whilst allowing flexibility to support customers with fluctuating needs. Highly tailored advice on customers’ job search processes helps individuals achieve their personally identified goals.

What’s not working well?

Disappointment can arise at times. Customers sometimes feel that they are working to a rigid or untailored action plan. This highlights that there can be communication difficulties between a customer and their employment adviser. When operating well, action plans are developed through mutual discussion and agreement. Other customers reported problems with the service’s messaging system, which is now being reviewed. Further frustration is caused by a minority of late and cancelled appointments, which can have a significant effect on a customer’s day. A final challenge is ensuring that customers have accurate and realistic expectations of the service when signing up. This report identifies recommendations for the service and details where these are already being implemented.

To what extent is Support to Work a standardised service, and how does tailoring take place within this?

The service operates to a basic skeleton model that we describe in the report. But, its strength lies in a focus on tailoring and adapting to meet individual circumstances. Positive customer experience often comes from the skills and flexibility of individual advisers to adjust how they work with different customers. Advisers use a range of approaches to give advice. This includes live and staggered feedback and practice interviews. The importance of tailoring underlines the value of investing in the interpersonal skills of employment advisers.

What is the staff experience like?

Advisers derive job satisfaction from noticing improvements in customers’ confidence and empowering customers with skills to navigate the job market independently. They enjoy working with customers who may not be able to access other services. Advisers believe that the voluntary nature of the service means customers are particularly engaged with its support. Support to Work customers choose for themselves when is the right time for them to be seeking help with finding work. At the same time, staff reported a shared frustration with the amount of time they spend setting and managing customers’ expectations.

What are the possible service gaps?

Analysis by the Department for Work and Pensions shows that disabled people are twice as likely as non-disabled people to fall out of work. Customers taking part in this research explained that it would be helpful to continue to access Support to Work’s help and advice even once they have been successful in securing work. Responding to this, from late 2020 Support to Work will begin to offer in-work support. This will be available to customers who enter employment during or shortly after using the service.

Additionally, many Support to Work customers are interested in identifying employers who have positive attitudes towards employing and supporting disabled people. There are now plans underway to introduce a jobs board element to the service. This will allow customers to search for jobs from employers who have made a commitment to inclusive practices. It will be open only to Scope customers. Customers gaining work through the jobs board will be able to remain in contact with an in-work adviser, allowing the service to monitor its success.

Summary

This evaluation finds that Support to Work offers a uniquely effective and empowering model of employment support for disabled people. The report highlights features of the service that facilitate positive outcomes. We hope it presents insights that are useful to both the direct stakeholders of the service and others working in the disability and employment world.

Introduction

Introduction to Support to Work

Support to Work is Scope’s national employment support service for disabled people. It supports disabled people who already have transferable skills and are actively looking for work.

It is a fully remote service. The customer communicates with their assigned employment adviser using telephone and digital tools.

The service runs for twelve weeks. During this time, the customer works with their adviser to develop and implement a plan of action to help them move towards their employment goal. Each ‘action plan’ is unique to the individual customer, but plans frequently include guidance and recommendations on:

- improving the customer’s CV

- crafting cover letters

- conducting job searches

- completing job applications

- interview practice and performance

- if, why, when and how to tell a prospective employer about a condition or impairment

- asking for reasonable adjustments

Scheduled appointments between the customer and adviser help the customer to implement and monitor progress on their personal action plan. Appointments may be held by telephone, Skype call, Skype instant chat or email. Appointments are supplemented by extra contact where necessary. This can take place via email, phone, or through a messaging function on the customer portal. The portal is an online space unique to each customer where they can store documents, send and receive messages, and access resources that their adviser has uploaded for them. Freely available information and advice on the Scope website also supports service provision.

Support to Work aims to help disabled people become more knowledgeable and skilled in their job search. It seeks to improve customers’ belief in their own capabilities and support them to apply for jobs they are truly interested in. Support to Work customers should also become aware or be reminded of their rights as a disabled person while looking for, or in, employment. Ultimately, the service aims to support disabled people into paid employment. In this evaluation we assess the ability of Support to Work to achieve these outcomes.

Introduction to the evaluation and its approach

This co-produced evaluation consciously takes a different approach to typical assessments of service performance.

Its unique approach and particular value come from the fact it has been directed and conducted by a team of people with lived experience of disability as well as those with professional evaluation expertise. Throughout the report this team writes as ‘we’.

This approach has allowed Scope to embed the knowledge, experience, needs and concerns of disabled people into how we value our services. As a team we have asked different questions and produced insights that can come only via the perspectives gained through lived experience of disability. These have directly informed how we judge Support to Work’s success.

As such, it is our belief that we have created an analysis and a set of recommendations that maximise the possible benefit of this evaluation to disabled people.

We have actively engaged with stakeholders of the Support to Work service at different stages of the evaluation process, seeking their views on:

- what information to collect (the research priorities)

- how and with whom to share evaluation findings

- how the service might respond to findings and the co-evaluation team’s recommendations

These stakeholders include Scope staff members linked to the service, the service funder, a past customer of the service, and a representative from a Disabled People’s Organisation providing employment support. Together they formed an Evaluation Stakeholder Panel.

For the research underpinning the evaluation, we applied both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Our sources and methods included:

- 14 individual interviews with Support to Work customers

- a focus group with 5 further Support to Work customers

- a focus group with 5 Support to Work staff members

- an interview with the Support to Work Programme Lead

- statistical analysis of pre- and post- service customer surveys

- statistical analysis of delivery data stored in the service database

- thematic analysis of free text data stored in the service database

We used the calendar year 2019 as the timeframe for our analysis.

The Appendix contains further information about methodology.

We aim to share more information on the co-production approach in a separate guide to co-produced research and evaluation at a later date.

Introduction to the report

This report presents the final findings from the evaluation research. We hope it presents insights that are useful to both the direct stakeholders of the service and others working in the disability and employment world. We find that Support to Work offers an effective and empowering model of employment support for disabled people. We aim to highlight features of the service that facilitate positive outcomes.

The report narrative starts with a focus on the characteristics and experiences of Support to Work customers and what enables them to engage with the service. We then examine where there might be barriers to people accessing Support to Work and explore how these could be addressed.

We go on to discuss the positive outcomes of the service, which include but are not limited to disabled people entering employment. This is followed by an in-depth analysis of what customers value most about the service, and conversely what’s not working so well.

Further into the report we consider to what extent Support to Work is offering a standardised service. We then zoom in on the staff experience within Support to Work and discuss how this supports the service’s goals.

Finally, we explore some possible gaps in the service and consider how these could be addressed.

Chapter 1: Who uses Support to Work?

Support to Work is targeted at customers who already have transferable skills but who are looking for some support with job searching, applications and interacting with a prospective employer. This contrasts with Scope’s face-to-face employment support services, which work with disabled people facing further barriers to entering employment.

The focus of Support to Work is reflected in the circumstances of people using it.

Time out of work

The length of time a customer has been out of work has recently been added as a data field in the customer management system. The available data indicates that the vast majority of customers using Support to Work have been in paid employment before.

Of the 94 customers completing Support to Work since the service started collecting this data, over half (55%, n=52) had been out of work for between 0 and 6 months – a relatively short time. As we explore in this chapter, customers in this category may be coming out of a longstanding position and need help navigating the jobs market.

The service also supports customers who have been out of work for much longer. Some customers have never been in paid employment. But, most customers joining the service have been out of work for fewer than 5 years. In future evaluations we will be able to report on these data with a larger sample size.

Demographics

Support to Work serves a diverse range of customers. The customer base is more ethnically diverse than the national disabled population, with customers of an Asian background particularly well-represented.

Note Data source

Data on the national disabled population was taken from the Office for National Statistics Labour Force Survey.

Fig 1.1: Ethnicity of Support to Work customers compared to the national disabled population

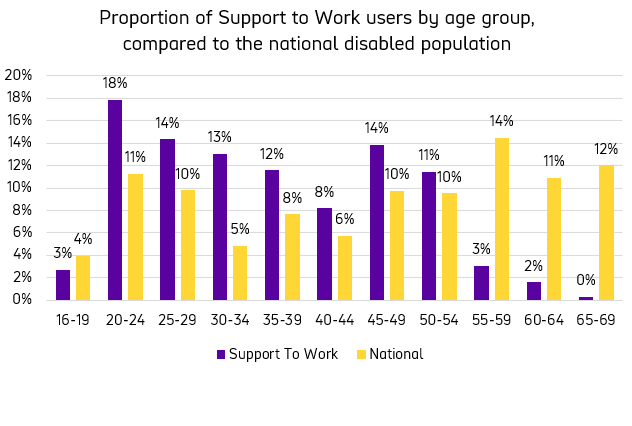

Support to Work customers are also younger than the national disabled population. This is partially explained by a large proportion of the national disabled population being over pension age. But, the proportion of Support to Work customers aged between 20 and 34 is substantially higher than the proportion of this age in the national disabled population.

Figure 1.2: Ages of Support to Work customers compared to the national disabled population

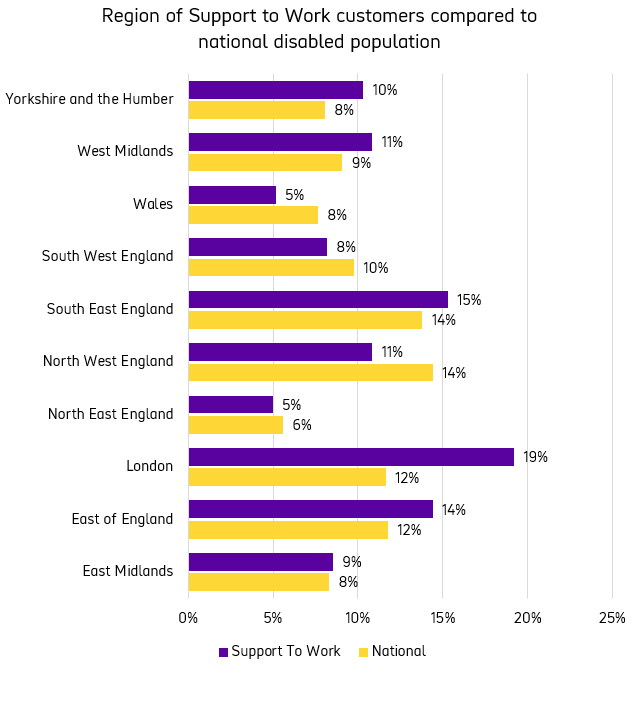

Interestingly, the location of Support to Work customers also differs slightly from the national disabled population. The proportion of customers living in London is higher than the wider disabled population (19% of customers compared with 12% of population). Conversely, the service has fewer customers in the North West and Wales than the national picture would suggest.

Note Use of ONS data

ONS data on only England and Wales was used, as Scope does not operate in Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Figure 1.3: Location of Support to Work customers compared to national disabled population

There is no significant difference in the gender breakdown of Support to Work customers compared with the national disabled population.

Experiences of employment

Most of the customers we spoke to as part of the evaluation had previous employment experience, mirroring the wider customer base. We also interviewed several people coming straight out of education.

Customers’ working histories were varied. They had worked in the public and private sectors and at many levels of responsibility and management.

It was striking that despite this range of employment backgrounds, people frequently shared negative and sometimes discriminatory experiences directly linked to them being disabled.

Participant 4

I’ve had a number of jobs over the past 2 years especially. And because I’m a registered nurse, all the jobs that I’ve had have been in healthcare. And my last job […] I had to leave on the grounds of disability discrimination.

Some had left jobs due to bad experiences when seeking reasonable adjustments following an acquired or worsening impairment. For many, leaving their previous job had been a protracted, upsetting and deeply undermining process during which they felt powerless.

Participant 13

My confidence has been dented as well because it's not something I've left of my own accord. It was due to long term sickness and they just terminated my employment because of my disability and sickness.

Participant 5

Unfortunately when I did ask for the reasonable adjustments, that then set out a chain of events that […] once they knew about my disabilities – the underneath ones – they decided it was probably better to get rid of me, and they did.

In these situations, the sense of loss customers feel at no longer being able to do their job in the same way is often compounded by the poor attitude of employers and wider society. For many it’s an emotional low point in their lives.

Participant 6

[Asking for reasonable adjustments] wasn't a very good experience to be honest. To be honest, this is part of the reason why I ended up out of work and struggling.

Focus Group Participant 1

I had to resign from my job because I physically couldn't do it any more, and that broke me, because I thought, I'd been working since 16 […] and just the feeling of being unemployed, there's such a stigma behind it, you know, and that's quite tough to deal with.

Several people we spoke to had negative experiences of the benefits system and the demands it places on them. Some did not qualify for disability benefits and so found themselves needing to generate income at a point when it was very challenging for them to do so.

Some customers had also had poor experiences of statutory employment support services mandated as a condition of receiving health and disability related benefits.

Note References

Previous reports by the Work Foundation (2016) and House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee (2017) document some of the negative experiences that disabled people have encountered in accessing state support related to disability and employment.

Sources:

Participant 2

[The job centre] kept on making me do work activity programmes where it was supposed to be leading [me] towards a job, and they did not help me for years.

The combination of many of these factors means that almost all evaluation participants reported having low confidence on joining Support to Work. Frequently, negative experiences in past employment or while seeking work have led directly to this decline in confidence. And our results suggest that low confidence affects customers regardless of their specific impairment or condition or how long they have been disabled for.

Customers have been made to lose confidence in themselves and their abilities, but also in employers and workplaces.

Note Reference

These qualitative findings chime with quantitative results of the 2008 Fair Treatment at Work Survey. The survey reported that 47% of disabled people who had a problem with unfair treatment at work, experienced a severe or moderate affect on their psychological health and wellbeing as a result.

Participant 10

I'd just completely lost all my confidence. I'd had a really bad experience [with my employer]. It was just a nightmare really.

Participant 3

My confidence was massively low, mainly due to the employment that I’d been in before.

It can also be hard for customers to acknowledge what they are no longer able to do.

Focus Group Participant 5

When you have physical disablement, you go through grief when you realise you can't do what you used to be able to do, and it's really hard, sometimes, to accept that.

Many people we interviewed did not find it easy to discuss these experiences.

Implications for the service

Prior experiences greatly affect customers’ feelings when joining Support to Work and the expectations they have of it.

Some customers’ primary emotion is one of relief. Many are simply thankful to have finally found help from people who seem to understand their situation. Sometimes, this relief and hope can lead to customers having very high expectations of what the service can help them achieve. Other customers may feel sceptical and tentative, especially if they have accessed other forms of employment support before. They may find it difficult to trust that their experience will be positive. Sometimes, customers find it hard to view themselves and their abilities positively.

Regardless of the specifics, the emotional impact of experiences features heavily in many customers’ interactions with Support to Work.

Focus Group Participant 5

Setting up your profile can be quite emotionally draining, you know, because you've got to sit and think about what you've got to do. Erm... for me the whole thing's emotional.

Focus Group Participant 2

[I wanted my adviser to] lead me, challenge me, convince me that I'm worth something, and help me to redo my CV to tell a positive message.

This has important implications for the service. It highlights the weight of expectation that customers can place on advisers to create a positive experience and ‘turn things around’. Indeed, as we discuss in chapter 8 on the staff experience, managing customer expectations is a large part of the role for advisers.

Alongside specific advice and guidance on the job search process, advisers’ sensitive, informed words on customers’ situations are often a deciding factor in whether a customer feels that they have had a positive experience with Support to Work. Chapter 5 on what customers value about the service explores this in more depth.

Our findings also highlight how important it is that advisers understand customers’ experiences, which can have a large effect on how the customer approaches the service. Advisers’ understanding can be important in building positive customer-adviser relationships. In turn, these positive relationships are central to achieving successful outcomes for customers.

Recommendation for future practice

Consider introducing a measure of self-confidence or self-esteem at the start of a customer’s journey, so that advisers gain a clear picture of a customer’s likely need for moral support and encouragement throughout the service. This could sit alongside customers’ self-ratings as part of the Workstar assessment (see note below) or in the baseline customer survey. Consider introducing a measure of self-confidence or self-esteem at the start of a customer’s journey, so that advisers gain a clear picture of a customer’s likely need for moral support and encouragement throughout the service. This could sit alongside customers’ self-ratings as part of the Workstar assessment (see note below) or in the baseline customer survey (see Appendix for more information about the baseline customer survey). The Evaluation team is in discussion with the Programme Lead about this proposal. For more information about the baseline customer survey). The Evaluation team is in discussion with the Programme Lead about this proposal.

Note What is Workstar?

The Workstar™ is a personal assessment tool used by the employment adviser and customer at the start and end of the programme.

It helps both parties understand the customer’s personal situation in 7 areas:

- job-specific skills

- aspiration and motivation

- job-search skills

- stability

- basic skills

- social skills for work

- challenges.

Chapter 2: What enables people to use Support to Work?

Our research showed that there are many factors influencing people’s ability to use and benefit from Support to Work:

- their digital skills, digital confidence and access to digital equipment

- the advertising or recommendation that led them to the service

- the sign-up information and process on the Scope website

- the tools of the service

- the culture of flexibility in the service

- customers’ individual personal circumstances and impairments or conditions

An aspect of these factors may make the service accessible or inaccessible for a particular customer. We discuss barriers to using Support to Work in the next chapter.

Here we present factors which support customers’ access and use of Support to Work.

Simple and friendly sign-up process

The customers we interviewed frequently felt positive about their route into Support to Work, including the sign-up process and their initial appointment. Customers appreciated that the service is voluntary and doesn’t require proof of disability.

Focus Group Participant 2

It was actually quite easy to go through the sign-on. There were no big hurdles, no big investigations... and it was quite joined up. And so I was connected very, very quickly.

Support to Work’s wide eligibility criteria, straightforward design and friendly non-judgemental approach were often in contrast to customers’ previous experiences of employment support. The stress and mistrust that people report experiencing when using support schemes offered by the Department for Work and Pensions has been documented several times.

Note References

The Work Foundation (2016) Is welfare to work, working well? Improving employment rates for people with disabilities and long-term conditions.

Participant 9

[When registering for Support to Work] I felt validated as a person. And it's very rare that you really get that in [employment support services]

Focus Group Participant 1

All the information was there, and every step was friendly. User-friendly, as well. You didn't feel like you needed to find out different words. Everything was easily signposted to know where you needed to go, so that was helpful. Coming from a person that's got learning difficulties and things […] you could simply find what steps you needed to take to get through to the end goal, so that was helpful.

Combination of phone and digital communication tools

It’s important to note that what may be a barrier for 1 disabled person can be the reason why Support to Work is accessible for another. This is particularly true of the phone and online based nature of the service.

Adviser

Some of our customers have social anxieties […] and I think having a service that's face-to-face wouldn't work for them. So having a service where you can speak over the phone or interact with us through the Scope portal and online and emails I think really helps with themselves as well, in terms of com[ing] out a bit more out their shell.

Participant 1

I am quite anxious if I have to make a phone call, it does take me quite a long time to build up... so the fact that I did have to ring up to get things done quickly did exacerbate things. But I quite liked the messaging system, that you've got on the portal. I found that quite a useful tool

Some customers found that the digital aspects of Support to Work particularly increased its accessibility for them.

Participant 12

And it's easier for me to do things online and over the phone, just for me, it's easier.

We acknowledge that the service’s reliance on digital tools can also be a significant barrier to some disabled people (as we discuss in the following chapter).

Flexibility

Customers we spoke to frequently made favourable comparisons with other employment support services. These positive comments often focused on the flexibility of Support to Work. The service gives these customers some control that they felt they had previously lost or been denied. Customers didn’t feel pressured to disclose information. They could change appointments without lengthy explanation or being made to feel as if they had failed. Their individual needs were taken into account.

Because disabled people often have only one way in which something can be made accessible to them, the flexibility offered by Support to Work is important. People’s access requirements can also change and fluctuate, so the responsiveness of the service is also critical.

Participant 12

We would organise each appointment, we'd then book the next one in. But also it was quite easy to change appointments. Like I say, chronic illness can be fun. And sometimes I had to kind of change appointments around if I hadn't got round to doing what I needed to do. […] Some services are a bit iffy about if you're cancelling appointments or moving appointments around. But yeah... [my adviser] was great at [offering] a lot of flexible times.

Emotional support

The emotional and moral support offered by Support to Work is vital to many customers and enables them to access the service and deem their experience successful. Advisers and customers generally agreed that the opportunity to build a relationship through the service supports this.

Focus Group Participant 5

I appreciated the help, with the [Workstar] visuals and everything else. It was more, for me, the emotional support.

It’s also important to acknowledge that there are limits to the emotional support that Support to Work can offer. Some customers needing additional emotional support may need to be signposted to other services.

Customer stories

Customer stories in adverts or on the Scope website made some of our evaluation participants feel more able to use Support to Work. Where this was the case, it was not because they had the same impairment or condition as the storyteller, but because they had had similar experiences and felt similarly about them.

Participant 1

[The customer stories] definitely made me more positive about referring myself.

Participant 10

Interviewer: So did you personally find reading the customer stories helpful? Customer: Yeah, I sometimes think it's that you're not on your own. That what you're going through, where it feels that you really are isolated at the time, other people have had similar struggles. It's not uncommon.

Having said this, we must also note that customer stories can sometimes have a negative effect on customers. This can occur when customers feel their experience with the programme has not been useful, pleasant or positive. In these situations, customers can sometimes internalise the root of their experience and feel that they are responsible for the service not leading to the outcome they wished for.

Participant 7

The stories look as though they've been successful in what they wanted to achieve. And then I did look at them after, and after I had my experience, I thought, 'Well I don't feel as though I've had that experience. What am I doing wrong?

We mention this as we feel it may shed light on some of the barriers customers face in staying with Support to Work for the full programme length. Customers’ cumulative negative experiences and historic discrimination may cause them to feel responsible for difficulties they face in accessing support or seeking adjustments. Their expectations of accessibility and their belief that access problems will be addressed may be low. They may choose to leave the service rather than seeking adjustments.

It’s important that Support to Work advisers repeatedly check whether there are any changes to how they provide their support that would help a customer’s continued use of the service.

The following chapter considers further barriers to using Support to Work in more detail.

Chapter 3: What stops people from using Support to Work?

Chapter 2 examined enabling factors that help people access Support to Work. To provide greater clarity on who can benefit from the service, here we present insight on people who leave the service early or who refer themselves but are not accepted onto the service.

Reasons for people not starting on the service

In 2019 Support to Work received referrals from 1958 unique customers. Of these customers, 621 started using the service. Some of these customers re-used the service within the calendar year. 1362 referrals to the service did not result in a customer joining the service.9

A data field recording reasons for customers not starting the service was added to the service database in mid-2019. Accordingly, there are quantified ‘did not start’ reasons for 259 customer cases in 2019. Of these, the most common is that the referring individual disengaged by failing to return phone calls or emails.

The Support to Work Programme Lead also performed a manual analysis on the full number of referrals received across 2019. This confirms the analysis performed on the partial data from the service database. The most common reason for referring individuals not starting Support to Work is a lack of contact. This can be a failure to respond to repeated messages or non-attendance at an initial appointment.

The Programme Lead’s analysis also shows that the second most common reason for non-starts is that the service is not suitable for the customer. Within this overarching reason, referring individuals may be:

- too young

- not disabled

- not looking for paid work (but rather work experience or volunteering)

- unaware that someone had referred them

- wanting a face-to-face service

- wanting to work with a recruitment agency

- wanting someone to write applications on their behalf

Finally, advisers deem some referrals (273 in 2019) ineligible for the service after speaking to them during an initial appointment. This ineligibility can be because:

- the customer has had a change of circumstances since their initial referral

- the self-assessment they provide as part of the Workstar indicates that the service is not right for them at that time.

Note What is Workstar?

The Workstar™ is a personal assessment tool used by the employment adviser and customer at the start and end of the programme.

It helps both parties understand the customer’s personal situation in 7 areas:

- job-specific skills

- aspiration and motivation

- job-search skills

- stability

- basic skills

- social skills for work

- challenges.

These combined reasons highlight that some people referring themselves to Support to Work have inaccurate ideas or expectations of what the service offers. Our qualitative research suggested that not everyone gains a clear picture of the service from its promotional material:

Participant 5

When you sign up to Scope or register your interest and stuff, they direct you towards the website. […] And I had a skim through it, and it's quite... it's hard to discern from that […] what the service is actually going to be like in practice.

Advisers also reported that they spend a lot of time managing customers’ expectations (as we discuss in Chapter 8 on the staff experience). Service expectations can also influence early exits from the service.

Reasons for leaving the service early

Some customers leave Support to Work before they have received the full 12 weeks of support. In some cases this is due to the customer gaining employment (see Chapter 4 for more detail on positive outcomes). Further reasons for exiting the service early are recorded by advisers in the service database as free text. This data illuminates barriers and external circumstances contributing to early exits. A range of reasons exist for the 268 cases of the service ending early in 2019.

Customer’s lack of communication or engagement

By far the most common reason recorded for early exits is not hearing from customers, echoing the main reason for customers that don’t start the service.

“[Customer] has been exited from the service as [they have] not responded to emails or calls. [They have] not attended any appointments beyond [their] second appointment.”

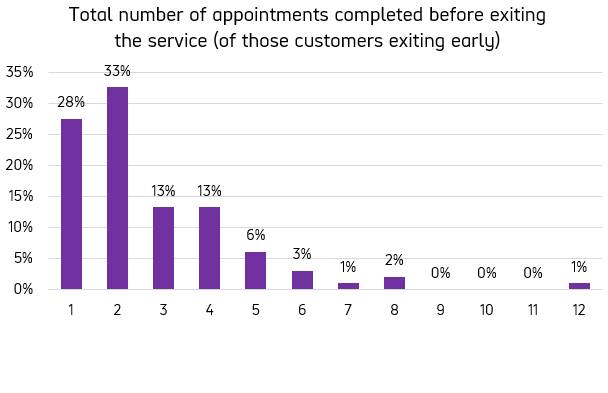

This particular free text record also reflects the fact that of the customers who leave the service early, the majority do so before their third appointment:

Figure 3.1: Total number of appointments that customers complete before exiting the service (of those customers exiting early)

When customers simply stop responding, it is hard to judge whether Support to Work could do something differently to support them. It’s possible that some disengagement is due to customers being unhappy with the service. Our qualitative research sheds light on some of the main causes of dissatisfaction within the service; see Chapter 6. But, it’s also possible that lack of commitment or engagement is caused by one of the following additional reasons for customers leaving the service early.

The customer no longer requires the service

Some customers leaving early choose to do so as they feel they no longer need support with finding employment.

“No longer needs support from the service as [they feel they] can move forward independently”

This chimes with comments from advisers who said they will close a customer’s case if they feel they are equipped with skills:

Adviser

For me, a successful customer is: anyone who knows how to write a good CV, knows how to write a good cover letter and applications […], very confident in interviews, knows how to disclose their disability […] if we’ve covered everything we said that we’d do, and we’ve done that in 6 weeks, I’d be happy to exit the customer, because we’ve done everything we can do for them, and they’ve been empowered with the skills.

This demonstrates that Support to Work can provide effective support within a rapid timeframe.

The service is not appropriate for the customer

Some customers leave Support to Work because they require in-person support or lack the digital confidence or skills to access the service fully.

“[Customer] had not uploaded [their] CV and said that [they] need support with this as [they] cannot do it [themselves]. We discussed our service in more detail and agreed that it is not the right service for [the customer] and that a face-to-face service would be more beneficial.”

Recommendation for future practice: The service should continue to maintain a list of sources of face-to-face support, so that onward signposting is possible for customers who would benefit from this. Support to Work may also want to consider maintaining information and resources on where customers can access support with using digital resources. Digital exclusion remains a widespread problem within the disabled population, with 42% of disabled people having a Low or Very Low digital engagement as measured by the UK Consumer Digital Index 2020. This is compounded by the fact that disabled people are 40% less likely to have received digital skills support from their workplace

Other customers ask to be exited from the service after realising that the service cannot provide things they were expecting, such as job brokerage or curated lists of vacancies.

“Customer unhappy I did not send [them] a list of jobs [they] can do based off [their] skills and experience.”

This was reflected in customer interviews, where we found that disappointed customers often started with an expectation of the service that went beyond what it offers. This emphasises the importance of clear, unambiguous marketing and supporting information about the service before someone becomes a customer.

Identified Action: We have recommended that the content explaining Support to Work on the Scope website is refined to highlight that the service cannot currently:

- offer job brokerage, where an adviser will liaise with a potential employer with the aim of securing the customer an interview, work trial or job

- source suitable vacancies for individual customers (other than while demonstrating how to conduct an independent job search)

- provide access to an exclusive list of ‘approved’ disability-friendly employers

- write a customer’s CV on their behalf, using information that the customer shares with their adviser

This content is being updated. We also recommend that the customer coordinator and advisers reiterate the service boundaries when a customer has their initial assessment. Taken together these measures should reduce:

- the number of people referring to the service but not commencing it

- the number of people leaving the service early

Outside commitments

Difficulty combining Support to Work with study, voluntary work or other services is another common reason for customers leaving early. This emphasises the importance of advisers supporting customers to understand the level of commitment necessary for full engagement with the service.

Health

A significant number of exiting customers cite ongoing health concerns as their reason for leaving the service early. This is a reminder that many disabled people have fluctuating conditions that can unexpectedly affect their ability to look for work. However, it may also represent the pressure that a lot of disabled people feel to find employment when the support they receive from the state is insufficient to support them, as one of our evaluation participants explained.

Participant 2

The government have left me no choice but to seek employment in some form or another.

Personal reasons

Finally, a wide range of personal issues are recorded as reasons for leaving the service early.

Likelihood of re-engaging

Positively, despite some customers asking to exit the service early, the free text records also show that many would access the service again. In many instances, advisers actively suggest and encourage this future engagement, enabling customers to feel welcome to return to the service when ready. We discuss the value of customers using the service at the right time for them in Chapter 8.

Data Quality

It is important to note that free text entries in the service database differ widely in the amount of detail recorded, depending on the individual contributor. This limits understanding of the main barriers to engaging fully with Support to Work. Additionally, the exclusive use of free text to capture reasons means that their aggregation and analysis take up a lot of time.

Identified Action: Using this evaluation data, the Evaluation team have proposed a set of core categories for early service exit reasons. The Programme Lead has added these categories as a reportable field in the service database, allowing exit reasons to be recorded in a standard format. The free text box that already exists for recording exit reasons will be maintained so that categorised data can be supplemented with further information where appropriate.

Identified Action: Support to Work is now recruiting a second customer coordinator who will be responsible for following up with Support to Work customers leaving the service. They will do this whether customers are exiting early or their time with the service has expired. This coordinator will record accurate destinations of these customers. We propose that they should also consistently record reasons for customers leaving the service. This should lead to greater understanding of the barriers that customers often face in accessing the service.

Chapter 4: What does Support to Work achieve for its customers?

One important aim of the evaluation was to explore what positive changes happen for customers as a result of using Support to Work. Our evaluation questions included a focus on outcomes that the service intends to achieve.

These include:

- disabled people entering employment

- disabled people gaining the knowledge and skills they need to choose, find and apply for jobs

- disabled people becoming confident of their capability in work

- disabled people knowing their rights when in, or looking for, employment

This chapter discusses these and related outcomes. We present the different outcomes in turn.

Disabled people entering employment

The ultimate goal of the service is to support disabled people into employment.

Focus Group Participant 3

I now have a job that I'm starting in about 2 weeks! Which I'm really proud of.

The service database stores information about whether a Support to Work customer enters employment when they leave the service. In 2019, 23% or 132 out of 578 exiting customers moved into work.

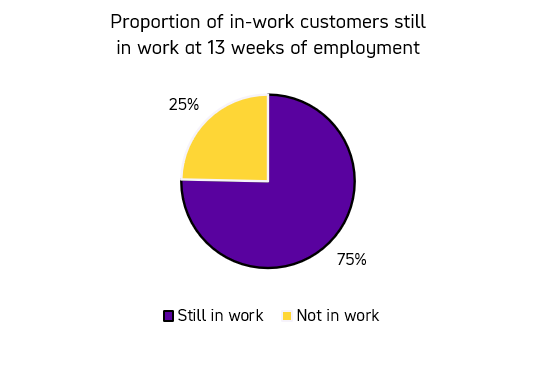

Advisers also contact customers who enter employment 13 weeks after they have started work, to gather data on whether they are still in employment. In the same period, 148 customers who had moved into work reached the 13-week milestone. Of these, Scope was able to reach 73 customers. 51% could not be contacted.

Of the customers we were able to reach, 75% were still in work after 13 weeks of employment.

We are confident that this is a representative picture of all customers reaching 13 weeks of employment, because when we analysed the data by different customer characteristics, the results were broadly the same.

Figure 4.1: Chart showing customer employment status at 13-week follow-up

The service does not currently monitor the employment status of all customers 13 weeks after they have left the service, only those who exit straight into employment.

Recommendation for future practice: The recruitment of a second customer coordinator, as mentioned in Chapter 3, should allow Support to Work to better monitor the eventual employment outcomes of all customers, not just those exiting straight into employment. Some customers may not find work whilst they are using the service but do so soon afterwards. Capturing this data would generate a more accurate picture of how many people enter employment after using Support to Work.

What kinds of jobs do people go into?

For customers who entered work in 2019, almost 3 quarters (73%) went into jobs of over 16 hours a week. 18% entered work of 8 to 16 hours, and 9% less than 8 hours per week.

Note 16-hour threshold

The 16-hour threshold is relevant as it is the maximum number of hours that someone can usually work while receiving Employment and Support Allowance, a disability related welfare benefit.

The types of jobs that customers enter vary. Using the Office for National Statistics Standard Occupational Classification 2010 (SOC2010) skill levels, the most common skill level of jobs that customers enter is Level 2. 51% of customers enter jobs at this level.

Note Occupation classifications

Figure 4.2: Jobs attained by Support to Work customers according to ONS SOC2010 skill level

Examples of jobs at different ONS Occupational Skill Levels

- Cleaner, catering assistant, hotel porter

- Carer, machine operator, administrative assistant

- Paralegal, electrician

- Corporate manager, doctor, lecturer

Note Reference

Taken from the Office for National Statistics website

When do people enter work?

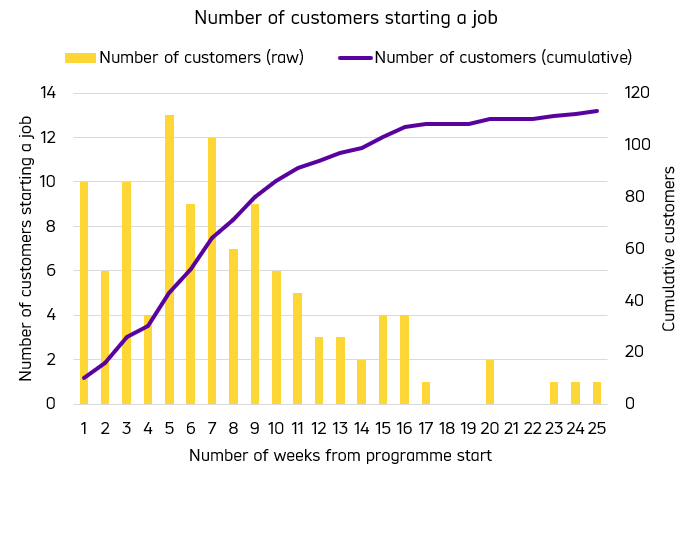

There is large variation in when customers start a job. The most common amount of time someone has used Support to Work before moving into work is 5 weeks. This may be explained by the responsive nature of Support to Work that allows customers to receive tailored support for specific tasks, such as an upcoming interview.

Figure 4.3: Number of customers starting a job at different lengths of time since starting the service

Are customers satisfied with the roles they go into, and do they keep their jobs?

The quantitative data presented above shows how many customers enter employment after using Support to Work. But, it cannot speak to whether customers are happy with their new job roles. Through interviews and analysis of case notes in the service database, we heard from participants who were pleased with their job and journey.

Participant 4

I’m now office manager. […] I couldn’t have asked for a better job or a better manager. You know, they’re completely understanding with my condition and I can sort of get up and go out when I need to and walk around the office […] I said to my manager last week actually, it’s probably the best job I’ve had since I qualified.

Case note excerpt from 13-week follow-up call

[Customer name] is enjoying [their] role at [employer] and was offered a permanent position in January 2020.

In contrast, one customer we interviewed reported that they did not continue with their new role.

Participant 6

Unfortunately, the job didn't really work out because of my health, but it was quite a good experience just kind of getting the job, going through the whole process. Because even though it could be quite stressful, it did give me a bit more confidence afterwards.

The case notes also revealed 2, 2019 customers, who had not stayed in employment.

Case note excerpt from 13-week follow-up call

[Customer] has handed in [their] notice and finishes next week Wednesday. The role is not suitable for [them] as there is no structure to the role.

The experience of these customers demonstrates that not all employment is sustained long term. A range of interacting factors can affect the longevity of job outcomes. Some of these factors may not be within the direct influence of Support to Work in its current form.

Participant 6 had a change to their health that affected their ability to stay in work. The customer from the case notes excerpt didn’t thrive in their work environment. These cases may or may not have been foreseeable. The situations could have potentially been worked around with the help of an understanding employer.

Regardless of the exact dynamics at play, the result was that these customers left recently gained employment. This is common. Analysis by the Department for Work and Pensions shows that disabled people are twice as likely as non-disabled people to fall out of work.

Further into this report, in Chapter 9, we explore the merits of customers maintaining contact with Support to Work even after entering employment. This could possibly help to reduce the incidence of people leaving jobs soon after gaining them.

What are some of the factors influencing employment outcomes?

Our research and analysis identified some factors that can influence whether someone enters work. This insight increases understanding of the service and may inform how we provide the service in future.

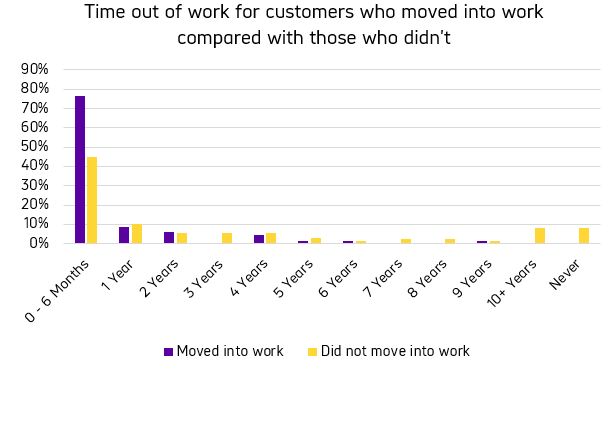

Time out of work

Deeper analysis of job outcomes showed that the number of customers moving into work varies substantially depending on the length of time the customer has been unemployed for. Figure 4.4 shows that fewer long-term unemployed customers enter work.

Most customers moving into work have only recently left a job. This suggests that the amount of time someone has been out of work is an important factor in influencing whether they find employment whilst using Support to Work.

Figure 4.4: Length of time spent out of work for customers who moved into work compared with those customers who didn’t

Customer confidence and perception of self at service entry

We also explored how customers’ baseline Workstar measures related to their employment outcomes.

Note What is Workstar?

The Workstar™ is a personal assessment tool used by the employment adviser and customer at the start and end of the programme.

It helps both parties understand the customer’s personal situation in 7 areas:

- job-specific skills

- aspiration and motivation

- job-search skills

- stability

- basic skills

- social skills for work

- challenges.

For every Workstar category, the baseline score was higher for customers who entered employment compared to customers who didn’t. This suggests that customers who start the service feeling more prepared for work are more likely to enter employment.

But, changes between the baseline and exit readings of all Workstar categories except ‘Basic skills’ also had a significant relationship with whether a customer moved into work. People who moved into work showed a larger change between their baseline and endline readings than those who didn’t. This demonstrates the contribution that Support to Work makes in equipping customers to find and enter work.

Wider circumstances

Customer interviews and the focus group highlighted some of the wider circumstances that can affect customers’ journeys into employment. These circumstances must be considered when judging what constitutes a successful outcome of Support to Work. The absence of eventual employment does not necessarily mean that the service has not been of value to the individual. There may be wider, structural barriers to employment outcomes.

Support to Work cannot directly influence:

- the attitudes of individual employers towards disability, age, or any other protected characteristic

- the accessibility of individual application processes

- local availability of jobs, public transport and childcare

- the boundaries of permitted work when receiving certain benefits

Note Employer attitudes

See Chapter 9 for information on what Scope is doing more widely to address employer attitudes and behaviour towards disability.

With or without Support to Work, these factors may have a large influence on how possible it is for a disabled person to enter employment.

Within these constraints, we heard from customers and staff alike that the service generates many positive outcomes aside from entering employment.

Adviser

If they haven’t got a job, it doesn’t mean the service hasn’t worked, because success is different things for different people.

We explore these in the rest of the chapter.

Disabled people gaining the knowledge and skills they need to choose, find and apply for jobs

Support to Work helps customers gain or consolidate the knowledge and skills they need to find employment. Customers can apply these skills to their job search both during and after using Support to Work.

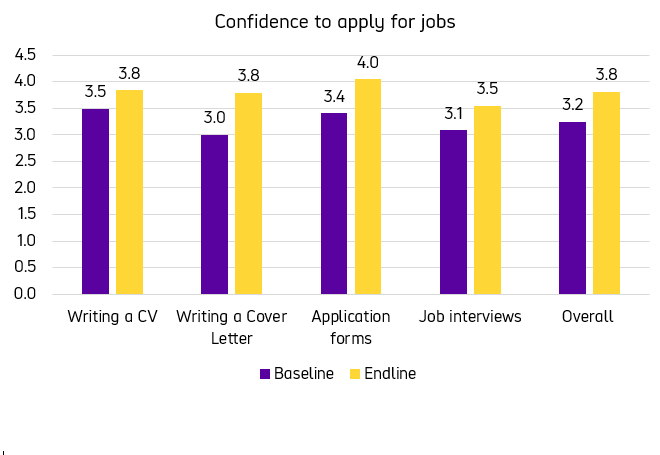

Data from baseline and endline customer surveys shows that customer confidence for job interviews, application forms, writing cover letters and writing a CV all significantly improve when using Support to Work (see the appendix for further detail on the methodology used in this analysis). This is shown in Figure 4.5. Responses are coded on a scale where 1.0 equals not at all confident and 5.0 equals very confident.

Figure 4.5: Confidence in different aspects of applying for jobs at baseline and endline (matched survey pair data)

Our qualitative data also offers rich evidence for this improvement in knowledge and skills. This can occur regardless of whether a customer enters employment.

8 participants reported greater knowledge and confidence in CV development. Customers spoke about receiving advice on content, formatting, and updating.

Participant 13

I haven't done many interviews or CVs […] so it was useful just to be able to say what the modern layout is, and [how] it might be presented and stuff […] so it's helped in that respect, in terms of just getting a document that might be appealing to prospective employers, making sure the information is clear and simple.

3 participants also spoke about new knowledge and skills for finding vacancies.

Participant 6

They kind of introduced me to quite a few different websites and ways of looking for jobs that were helpful, and obviously I’ll be carrying that on if I’m looking for a job in the future as well.

One participant specifically mentioned application forms and how they’ve used new skills independently after accessing Support to Work.

Participant 14

We filled in job application forms together, and I feel that if I was applying for a job by myself and I needed to fill out an application form, I’d be confident enough to be able to sort of do it on my own.

Customers reported interview skills as a particularly useful outcome of using Support to Work, with 5 participants reflecting on this especially. Holding a mock interview was particularly valued.

Focus Group Participant 1

Doing the practice interviews over the phone sort of made you think more about what you were saying, and how you were to try and sell yourself more.

In Chapter 7 we go into more detail about features of the service that link to these knowledge and skills outcomes.

Disabled people becoming confident of their capability in work

In our research, customers and staff referred frequently to changes in self confidence, mindset and how customers see themselves through accessing Support to Work.

Improvements in confidence and self-belief were some of the strongest outcomes reported by evaluation participants.

Focus Group Participant 2

It's been, as I said, that momentum, that confidence, that I've got from the service.

Participant 12

[My adviser] particularly helped that kind of increasing my belief that I was actually going to be able to do a job. Because there were sometimes, you'd kind of get responses from people that were a bit iffy on disability stuff […] that slowly chip away, further and further at your confidence and how you feel about your ability to work.

The customer baseline and endline surveys also demonstrated that, on average, customers gain confidence in their capability to perform well in a job after using Support to Work. On a standardised scale of 1.0 to 5.0, on average customers improved in their confidence from 3.69 to 3.87. There was an improvement for every question asked.

This is further reflected in survey data showing that customers apply for more jobs that are ‘interesting’ and ‘a good step for my career’ after accessing the service.

Participant 10

I was putting everything really in to trying to get this job, because it's the one I really wanted.

Confidence links closely to a sense of empowerment. This was a theme that both customers and staff referred to in our research. Empowerment means that someone has gained the power to do something for themselves. It comes from a combination of knowledge and confidence.

3 participants talked about empowerment as a success of the service.

Participant 4

If you want to pinpoint anything it would be the fact that I felt enabled to do things for myself. […] Even though the skills were already there, but I felt like I had the power to do it and change it myself.

Processes of empowerment ensure that customers aren’t just learning but feel able to apply new knowledge and skills independently, both during and after the service.

Appropriate tailoring of tasks and action plans is part of what encourages empowerment. Different customers need varying levels of encouragement, support, and guidance before they can move towards independent actions.

This underlines the importance of realistic and supportive action plans, which we talk more about in Chapters 5 and 7.

Disabled people knowing their rights when in, or looking for, employment

Support to Work aims to improve customers’ knowledge of their employment rights as a disabled person. If customers know what rights they have and how they can respond when their rights are infringed, they may be less likely to have to leave or change jobs – as many Support to Work customers have already had to do.

Not all customers we interviewed actively wanted advice on their rights. Some customers were already confident in their knowledge and application of rights, while others felt it wasn’t relevant to them at the time.

Participant 4

I’d had so many jobs over the last sort of 2 to 3 years […] and after the last experience that I had, that in itself made me more confident any way to ask for [adjustments]

But, other customers clearly appreciated being able to talk through not only the details of equalities law, but also practical ways to discuss disability with an employer.

4 customers specifically mentioned their adviser helping them to develop a clear, individual strategy for disclosing their impairment or condition and asking for reasonable adjustments. Rather than an improvement in knowledge of rights, this reflects more a confidence in using rights to one’s practical advantage:

Participant 6

One of the other things that they really helped with was having a good discussion about whether to disclose my mental health at work and the kind of experiences I had before that. Which I found that really helpful as well. […] And to be honest, [the strategy we discussed] has worked out quite well.

Participant 3

This is something that [my adviser] and I spoke about […] not mention at interview but once, you know, if somebody was actually accepted into the workplace then mention, by the way, you know, I’ve got epilepsy, just wanted to make you aware of this, and I do have seizures, at the moment they’re these type of seizures.

This is echoed in customer survey data showing a small improvement in customers’ confidence to ask a manager for reasonable adjustments after using Support to Work. Advisers’ understanding of disability and anticipation of possible needs that we discuss in Chapter 5 helps advisers present useful ideas to customers.

One customer we interviewed felt that Support to Work didn’t help them learn about their rights.

There was no significant change in the number of customers answering factual employment rights questions correctly in the customer survey, and so there is no quantitative evidence for this outcome.

We have since updated the questions used to measure knowledge of rights. The previous measure was much simpler and may have been too blunt to capture changes. The updated measure should allow future evaluations to contain more detailed analysis of knowledge in employment rights.

One participant felt they may want to come back to Scope for additional advice on rights in the future, perhaps when in work. We discuss the demand for in-work support in Chapter 9.

Chapter 5: What do customers value most about Support to Work?

Our customer interviews and focus group shed light on features of Support to Work that customers value highly. These elements all contribute to customer satisfaction and sustained engagement with the service. They are likely to be associated with greater probability of positive employment outcomes.

We have organised the features into 3 broad categories:

- The skills and experience of the Support to Work advisers.

- The tools and underlying format of the service.

- The central focus on tailoring to the individual.

These features tend to support and overlap with each other when the service is working optimally.

The skills and experience of the Support to Work advisers

At the heart of the service sits the working relationship between a customer and employment adviser over a twelve-week period. This makes adviser skills and experience critical to customers’ successes. Customers place great value on the following.

Listening skills

Satisfied customers feel that their adviser makes an effort to truly hear and understand their unique situation. Understanding someone’s circumstances involves listening to their hopes, concerns, experience and skills. A significant number of evaluation participants praised the listening skills of their adviser.

Participant 2

He was a really good listener. He understood what I could and couldn't do, and he kind of worked his head around it.

Participant 6

It was just nice to have somebody that felt really genuinely interested and sort of engaged in the whole thing.

Advisers take customers’ experiences on board through this attention to listening. They also ask sensitive questions to uncover further information when appropriate. This helps to build an even broader picture of a customer’s circumstances.

Focus Group Participant 1

I was sort of explaining the issues that I’ve got, and he was understanding. And then if he didn’t know, he asked, which was helpful, because […] he was aware that he wanted to get the understanding to sort of build on that relationship more.

The offering of a new perspective and new ideas

The genuine effort to listen to and grasp a customer’s circumstances helps advisers reframe someone’s situation. Advisers apply what they have learned from conversations. They highlight positives that the customer may not have considered before, or which they currently find it hard to focus on.

A new angle on things can transform how customers feel about their job search and the possibility of gaining work. It can be particularly powerful for customers who are feeling constrained in their options and who have lost confidence in themselves. As discussed in Chapter 1, this might be the case if the customer has had to leave their previous role due to changes in their condition or impairment, or because of an employer’s negative response to such changes.

Such customers talk about the change in outlook that their adviser helps them reach:

Focus Group Participant 5

Part of the mindset of going from 'I can't do this,' and feeling very negative, but then getting to the point where I thought, 'I can do this,' […] the [adviser] was good at that, in being able to help me with being realistic, but also help me feel positive to do the realistic stuff.

Participant 10

It was really focused on, ‘Right, let's have a look at what your skills are, let's have a look at what you can offer'. And it was very much focused on the can-do rather than, 'Oh, you won't be able to do this' sort of attitude. Because I was very aware of what my limitations would be.

Many customers also appreciate their adviser presenting novel ideas. When Support to Work is working at its best, advisers are highly tuned in to someone’s experience, aspirations and apprehensions. They combine this understanding with their employment market knowledge to suggest alternative ways of reaching goals. New ideas might directly relate to a job search or could be more widely supportive of someone’s situation. As an example, here an adviser helps a customer access the disability benefits she was entitled to:

Participant 3

She actually pointed out things that I hadn’t even thought about at all and got me some ideas that I took away with me. I managed to get onto something called PIP actually […] And so I do thank [my adviser] a lot for that. It’s not something that I’d even thought about.

Customers highlight how ideas are presented as helpful suggestions rather than directions on the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ ways of doing things. We revisit this observation later in this chapter under ‘Central focus on tailoring to the individual’.

Acceptance and understanding

Customers also commend how Support to Work advisers demonstrate acceptance and understanding.

Many disabled people using Support to Work have encountered alternative employment programmes elsewhere. They may also have applied for state support as a disabled person. Customers emphasised the contrast between other forms of support and Support to Work. The contrast is palpable when entering the service, even before building a relationship with an adviser. Support to Work’s open eligibility criteria contrast positively with the need to provide proof of disability or financial hardship before using other sources of support.

Participant 6

It was a case that it was if you felt you had a disability, rather than having to prove it or anything like that – I guess that was what attracted me the most.

Focus Group Participant 3

I remember trying to apply to several different employment services, but I would never really fit the criteria, because I was either ever so slightly too old, or I didn't have anxiety and depression diagnosis so I wouldn't qualify for them, […] or it would be, I would have to be on benefits in order to receive it […] so yes, I was quite relieved to find a service that I actually fit the criteria for.

Then, when working with their adviser, customers often feel relief that they understand the challenges that disabled jobseekers can face. Advisers grasp that many of these challenges arise from social barriers. They work from the frame of the social rather than medical model of disability. The social model says that people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their impairment or difference.

More information about the social model of disability on Scope's website.

Some customers may not be aware of the social model before using Support to Work. Advisers’ understanding of this perspective is another important way that they can help a customer positively reframe their situation.

Over time, advisers have built up knowledge and understanding of a broad range of disabled people’s challenges in finding work. This means that they can often anticipate likely needs in advance.

Participant 12

I think it helps, knowing that they've spoken to other people before […] you don't have to go through the first steps to explaining everything about conditions and everything about this. They kind of know the broader umbrella [of things] that a lot of people can struggle with.

Although advisers should always listen and respond to each person’s unique situation, this ability to anticipate needs means advisers can be ready to support someone with common difficulties. Advisers with lived experience of disability also contribute a unique empathy with customers’ challenges and deepen the level of understanding within the service. In 2019, half of the Support to Work team were people with lived experience of disability.

Finally, simply acknowledging someone’s challenges can help customers feel validated:

Participant 11

I've been [looking for work] for 2 years now, and I'm coming up against all the same problems. And when I'm asked to go into the job centre, their attitude is very much that these are problems that I shouldn't be having […] So the fact that my adviser comes up against the same challenges that I do is then quite reassuring to me.

Advisers’ commitment to acceptance and understanding overlaps with the service’s focus on individually tailored action plans. We discuss this in the last part of this chapter.

The tools and underlying format of the service

Customers also value how Support to Work is structured and what this means when working with their adviser.

Not everyone thrives using every part of the service structure and supporting technology. So, advisers adapt to work in the way that suits each customer best. We discuss this more in Chapter 7. Here are some of the structural features of the service that customers appreciate.

The online customer portal

Customers who feel able to engage with their online portal find it useful as a central place to share, store and find all documents and resources relevant to their job search. Customers looking for specific pieces of information (for example, on disability-friendly employers) can access resources that their adviser uploads for them.

Focus Group Participant 5

It made, I think, my anxiety a lot less, because I could see clearly in front of me, it was all there. Every time we had a meeting on the phone, [my adviser] would refer back to, ‘OK, open that file.’ […] so I really appreciated that. I thought it was really helpful and took away a lot of stress.

Other customers particularly like the portal for its messaging system, especially when they feel too anxious to make a phone call.

It’s important to note that not all customers find the portal useful. We cover this in more detail in chapter 6.

First-hand practice of workplace skills